Maize silage generally has a higher biogas yield per fresh tonne than grass silage due to its higher energy content, particularly from starch-rich grains. However, the total yield can vary depending on factors like the specific plant variety, harvest time, and how the silage is prepared.

Key Takeaways Re: Biogas Yield from Maize Silage vs Grass Silage

- Maize silage dominates the biogas industry with approximately 55% market share in countries like Germany due to its consistently high methane yields of up to 0.38 m³/kg.

- While maize silage offers superior biogas production efficiency, it creates environmental concerns including monoculture problems, high fertilizer requirements, and competition with food production.

- Grass silage presents a promising alternative with high-quality methane content (70-80%) and better landscape integration, though it generally produces lower yields per hectare.

- The economic viability of grass silage is challenged by higher harvesting and transport costs despite its environmental advantages.

- Co-digestion strategies combining different feedstocks can optimize biogas operations while reducing environmental impact.

Biogas production stands at a crossroads. As of late 2014, approximately 8,000 biogas facilities operated in Germany alone, with the majority relying heavily on maize silage as their primary feedstock. The current landscape reveals both opportunities and challenges as producers consider alternatives to the dominant maize silage paradigm.

The renewable energy sector continues to evolve rapidly, with biogas playing an increasingly vital role in our sustainable energy future. Silage selection fundamentally impacts not only methane yields but also broader ecological and economic considerations that savvy producers must weigh carefully. Understanding the complex tradeoffs between maize and grass silage can empower informed decision-making for biogas operations of all scales.

Article-at-a-Glance

The biogas industry faces growing pressure to balance productivity with sustainability. While maize silage currently dominates the sector with approximately 55% market share in countries like Germany, alternative feedstocks such as grass silage are gaining attention for their potential to address environmental concerns. This comprehensive comparison examines the critical factors that influence biogas yield, methane quality, economic viability, and ecological impact of both feedstock options.

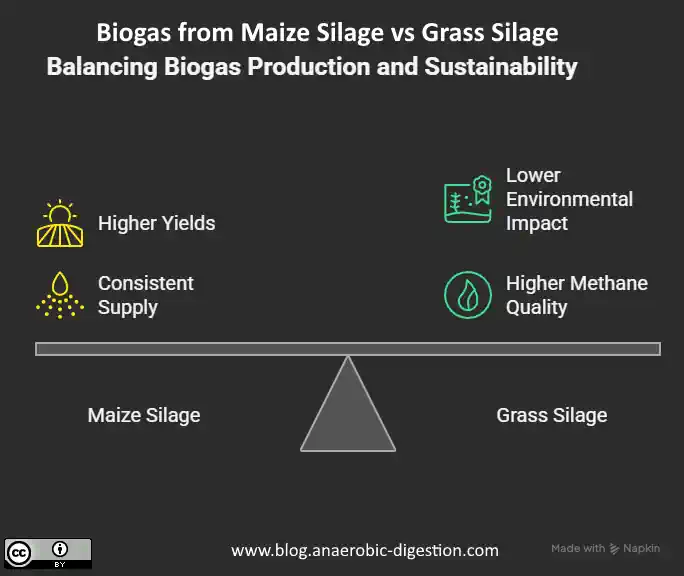

Biogas Production Comparison at a Glance

Maize Silage: Higher yields per hectare, consistent year-round supply, 55% market share

Grass Silage: Lower environmental impact, utilizes marginal land, high methane quality (70-80%)

Key Challenge: Balancing optimal biogas production with sustainable land management practices

The renewable energy landscape continues evolving rapidly as we search for sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels. Anaerobic digestion (AD) for biogas production represents one of the most versatile technologies available, converting organic matter into methane-rich biogas while producing nutrient-rich digestate as a valuable byproduct. The feedstock selection fundamentally shapes both the operation's efficiency and its broader impact.

Maize vs Grass Silage: The Battle for Better Biogas Yields

“CORN vs GRASS SILAGE – CHEAPEST …” from www.youtube.com and used with no modifications.

The fundamental question facing biogas producers today isn't simply which feedstock produces more gas—it's about finding the optimal balance between productivity, sustainability, and economic viability. Maize silage has earned its dominant position through consistently high yields and proven performance in digesters. Yet as environmental concerns mount and land-use conflicts intensify, grass silage has emerged as a compelling alternative that addresses many of maize's shortcomings, albeit with productivity tradeoffs that must be carefully considered.

What Makes Maize Silage a Biogas Powerhouse?

The dominance of maize silage in biogas production isn't accidental—it's rooted in the crop's exceptional performance characteristics. As the industry standard, maize silage consistently delivers high methane yields that provide operators with predictable energy outputs. This reliability forms the financial backbone of thousands of biogas operations worldwide.

Higher Methane Production Per Ton

Maize silage consistently outperforms alternatives in methane yield per unit of organic material. Research demonstrates that properly ensiled maize can produce methane yields of 0.25-0.38 m³ per kilogram of volatile solids, representing some of the highest conversion efficiencies available from crop-based feedstocks. This exceptional productivity stems from maize's high starch content and favorable carbon-to-nitrogen ratio that creates ideal conditions for methanogenic bacteria. The material's homogeneity also contributes to more stable digestion processes with fewer inhibitory factors to impede gas production.

Greater Hectare Yields Than Alternatives

When measuring total energy output per land area—a critical metric for large-scale biogas operations—maize silage maintains a significant advantage over grass alternatives. A single hectare of well-managed maize cultivation can produce enough biomass to generate 5,000-9,000 cubic meters of methane annually. This exceptional land-use efficiency explains why maize has become the cornerstone of industrial biogas production despite growing environmental concerns. The crop's ability to efficiently convert sunlight, water and nutrients into readily digestible biomass remains unmatched among temperate climate energy crops.

Consistent Energy Content Year-Round

Operational stability represents another key advantage of maize silage in biogas facilities. Once harvested and properly ensiled, maize maintains consistent fermentation characteristics for 12+ months, providing year-round feedstock availability with minimal quality degradation. This predictability allows plant operators to maintain stable biological processes in their digesters, avoiding the productivity losses associated with frequently changing substrate characteristics. For commercial-scale operations with continuous production requirements, this reliability translates directly into improved financial performance and reduced operational risks. To learn more about maintaining efficiency, check out advantages of digestate separation.

The Dark Side of Maize Silage Dominance

Despite its productivity advantages, maize silage comes with significant drawbacks that have increasingly concerned environmental scientists and policymakers alike. The expansion of maize cultivation specifically for biogas production has transformed agricultural landscapes across Europe and beyond. Germany alone has dedicated over 900,000 hectares to energy crop production, with maize comprising the vast majority of this acreage.

Monoculture Risks and Biodiversity Loss

The intensive cultivation of maize in large monocultures creates ecological vulnerabilities that threaten both agricultural sustainability and natural biodiversity. Year-after-year maize production on the same fields depletes soil organic matter, alters microbial communities, and increases susceptibility to pest outbreaks. The uniform crop structure provides minimal habitat diversity for beneficial insects, birds, and small mammals, effectively creating biological deserts across the landscape. Studies have documented significant reductions in farmland bird populations and insect biomass in regions where maize cultivation has intensified for biogas production.

High Water and Fertilizer Requirements

Maize demands substantial inputs to achieve the high yields that make it attractive for biogas production. Water requirements can reach 500-800mm during the growing season, often necessitating irrigation in drier regions and straining local water resources. Nitrogen fertilization typically ranges from 150-250 kg/ha annually, contributing to groundwater contamination and nitrous oxide emissions—a greenhouse gas approximately 300 times more potent than CO2. The carbon footprint associated with synthetic fertilizer production further undermines the renewable energy credentials of maize-based biogas systems, reducing their net climate benefits. For more information on how biogas production can impact the environment, read about anaerobic digestion's role in reducing landfill reliance.

Land Competition with Food Production

Perhaps the most contentious issue surrounding maize silage for biogas involves the “food versus fuel” debate. Prime agricultural land diverted to energy crop production reduces capacity for food production, potentially affecting food security and prices. This conflict intensifies in regions with limited arable land resources, forcing difficult societal choices between energy and food priorities. As global population continues growing alongside climate pressures on agricultural productivity, the ethical implications of dedicating fertile farmland to biogas feedstock production have drawn increasing scrutiny from policymakers and sustainability experts.

Grass Silage: The Promising Alternative

In response to the environmental limitations of maize monoculture, researchers and industry innovators have increasingly turned to grass silage as a more sustainable alternative. This transition represents not merely a substitution of feedstocks but a fundamental rethinking of how biogas production can integrate with landscape management and ecological priorities. Recent studies have demonstrated that grass silage can produce high-quality biogas while offering numerous environmental co-benefits.

Landscape Integration Benefits

Unlike maize, which creates monoculture landscapes, grass production systems contribute positively to landscape diversity and aesthetic quality. Permanent and semi-permanent grasslands provide habitat continuity that supports pollinators, ground-nesting birds, and diverse plant communities. The deep, fibrous root systems of perennial grasses improve soil structure while reducing erosion on sloped terrain where row crops like maize would create significant runoff issues. This multifunctionality allows biogas production to align with broader environmental objectives rather than conflicting with them, creating opportunities for truly integrated landscape management.

Lower Environmental Footprint

Grass silage production typically requires significantly lower chemical inputs than intensive maize cultivation. Fertilizer requirements can be reduced by 30-50%, particularly when leguminous species are incorporated into grass mixtures. The perennial growth habit of many grass species minimizes soil disturbance, thereby reducing carbon losses and improving sequestration potential. These combined benefits substantially improve the lifecycle carbon footprint of grass-based biogas systems compared to maize alternatives. Water quality also benefits from reduced nutrient leaching and year-round ground cover that filters runoff before it reaches waterways.

Utilizing Otherwise Unused Resources

One of the most compelling advantages of grass silage involves its ability to utilize marginal agricultural land and landscape maintenance byproducts that would otherwise go unused. Grasslands can be productively established on flood-prone areas, steep slopes, and other locations unsuitable for annual cropping, effectively expanding the land base available for biogas feedstock without competing with food production. Research at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology has confirmed that material generated through regular landscape maintenance activities can be effectively utilized for biogas production, creating value from what would otherwise be a waste management challenge.

Roadside verges, conservation areas, and public green spaces generate substantial biomass through necessary maintenance operations that traditionally represented disposal costs rather than revenue opportunities. Converting this material to biogas feedstock transforms a liability into an asset while avoiding the dedicated land requirements of purpose-grown energy crops. This approach effectively decouples some biogas production from agricultural land competition, addressing one of the fundamental sustainability challenges facing the industry. Learn more about how anaerobic digestion reduces landfill reliance and supports sustainable practices.

Municipal and landscape authorities can potentially offset maintenance costs by supplying this material to biogas operators, creating economic synergies across sectors while advancing circular economy principles. Several European regions have already implemented pilot projects that demonstrate the feasibility of this approach, though challenges remain in optimizing collection logistics and ensuring consistent biomass quality.

Where Grass Silage Falls Short

- Lower biomass yields per hectare compared to maize

- Increased harvesting complexity with multiple cuts per season

- Higher transportation costs due to lower energy density

- More variable composition affecting digester stability

- Seasonal availability challenges requiring storage solutions

Despite its environmental advantages, grass silage presents several operational challenges that have limited its adoption as a primary biogas feedstock. These limitations are primarily economic and logistical rather than technical, as the material can certainly produce high-quality biogas under proper management conditions. Understanding these constraints is essential for operators considering a transition away from maize-dominant feedstock strategies.

The economic viability of grass silage often depends heavily on local conditions, including transportation distances, existing equipment availability, and regional support mechanisms for sustainable biogas production. Operations located in regions with abundant grassland resources and favorable policy environments may find grass silage economically competitive despite its inherent productivity limitations.

Technology developments in harvesting, preprocessing, and digester design continue improving the performance gap between grass and maize silage, with some innovative operations achieving comparable economic outcomes through optimized system integration. These pioneering facilities demonstrate that with proper planning and infrastructure, the limitations of grass silage can be substantially mitigated.

Lower Specific Biogas Yields

When comparing direct biogas production potential, grass silage typically yields 10-30% less methane per ton of dry matter than maize silage. This productivity gap stems from grass's higher lignocellulose content and lower readily available carbohydrates, creating a more challenging substrate for anaerobic digestion. The specific methane yields from grass silage generally range from 270-350 litres per kilogram of volatile solids, compared to 300-380 litres for maize silage, though these values vary significantly based on grass species, harvest timing, and ensiling conditions.

Higher Harvesting and Transport Costs

The economics of grass silage are further challenged by increased operational expenses throughout the supply chain. Unlike maize, which provides a single high-volume harvest annually, grass production typically requires multiple cuts throughout the growing season, multiplying equipment and labour requirements. Each cutting operation incurs fixed costs for machinery mobilization and operation, regardless of yield, creating higher per-ton production expenses. These challenges highlight why some regions, like Northern Ireland, are exploring alternative solutions to optimize production costs.

Transport efficiency similarly suffers due to the lower energy density of grass compared to maize. This translates to more trips, higher fuel consumption, and greater logistics complexity to deliver equivalent energy content to the biogas facility. For operations with feedstock sourced from distant locations, these transportation penalties can significantly impact overall economic viability and carbon footprint.

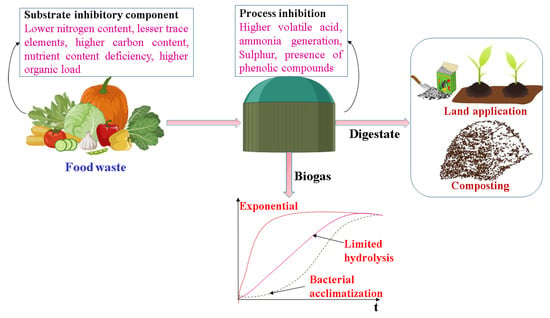

“Food Waste for Bioenergy Generation …” from www.mdpi.com and used with no modifications.

Seasonal Variability Challenges

While maize silage maintains relatively consistent characteristics throughout the storage period, grass silage exhibits greater variability both within and between harvest seasons. The nutritional profile and digestibility of grass changes dramatically throughout the growing season, with early cuts providing higher protein content and digestibility while later harvests yield more fiber and lower nitrogen. These variations can disrupt digester biology when not properly managed, potentially reducing gas production efficiency.

Weather vulnerability represents another significant seasonal challenge, as optimal harvest windows for grass can be narrow and highly dependent on favorable conditions. Rainfall during harvest can reduce dry matter content and silage quality, while drought periods reduce overall yields. These weather dependencies increase operational risks compared to maize production, where the harvest window offers greater flexibility.

Managing consistent digester performance with variable grass silage requires more sophisticated monitoring and process control systems than many existing facilities have implemented. Operators must carefully blend feedstocks and adjust loading rates to maintain stable biological conditions when substrate characteristics change significantly between batches. For those interested in advanced solutions, exploring digester cleaning services might provide additional insights into maintaining optimal conditions.

Real Numbers: Biogas Yield Comparison

When evaluating feedstock options for biogas production, concrete performance metrics provide essential decision-making guidance. Research data consistently demonstrates maize silage's productivity advantages while highlighting grass silage's quality benefits. These empirical findings help operators quantify the tradeoffs involved in feedstock selection and identify opportunities for optimization.

Laboratory analysis across multiple European research facilities has established reliable benchmarks for biogas potential from various silage types. These standardized tests measure biological methane potential (BMP) under controlled conditions to determine maximum theoretical yields. While real-world performance typically falls 10-15% below these laboratory values due to operational inefficiencies, the relative performance differences between feedstocks remain consistent.

Field trials conducted by biogas operators provide additional insights into practical performance under commercial conditions. These real-world tests incorporate the effects of equipment limitations, operational constraints, and management decisions that laboratory studies cannot replicate. The combined knowledge from both laboratory and field research creates a comprehensive understanding of feedstock performance potential.

Methane Content and Quality

One area where grass silage demonstrates competitive advantages involves the quality of biogas produced. Studies have shown that grass silage consistently generates biogas with methane concentrations between 70-80%, compared to typical values of 50-55% for maize silage. This higher methane content increases the energy value per cubic meter of biogas and reduces purification requirements for applications like grid injection or vehicle fuel. The superior methane concentration appears linked to the balanced nutrient profile of grass materials, which supports more efficient methanogenic microbial communities.

Comparative Biogas Yield Data

Maize Silage: 170-200 m³ biogas/ton fresh matter | 50-55% methane content

Grass Silage: 120-150 m³ biogas/ton fresh matter | 70-80% methane content

Theoretical Energy Yield: Maize silage produces approximately 15-20% more energy per ton despite lower methane concentration

Energy Return on Investment

When considering the full lifecycle energy balance, grass silage often narrows the performance gap with maize. The energy return on investment (EROI) – the ratio of energy output to input – typically ranges from 3:1 to 5:1 for maize silage systems. Grass silage systems can achieve similar or better EROI values of 4:1 to 7:1 due to lower cultivation energy requirements, particularly for perennial systems that eliminate annual planting operations. This improved energy efficiency becomes increasingly important as the renewable energy sector faces greater scrutiny regarding net carbon impacts and true sustainability credentials.

Carbon footprint analyses further highlight grass silage's environmental advantages. While maize silage-based biogas typically reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 60-70% compared to fossil fuels, grass silage systems can achieve 70-85% reductions when proper management practices are implemented. This improved climate performance stems from reduced fertilizer requirements, enhanced soil carbon sequestration, and lower field operation intensity for established grasslands.

Economic Realities of Silage Choice

The financial viability of biogas operations ultimately determines which feedstock options gain market traction. Current economic structures often favor maize silage despite its environmental limitations, though policy changes are gradually shifting this balance. Understanding the complete cost structure of different silage options helps operators identify optimization opportunities and anticipate future market developments.

Production Costs Breakdown

Maize silage production costs typically range from €25-35 per ton of fresh material, with seed, fertilizer, and harvesting representing the largest expense categories. By comparison, grass silage production costs vary more widely from €20-40 per ton depending on management intensity, with multi-cut systems at the higher end of this range. While establishment costs for perennial grass systems exceed annual costs for maize, these expenses amortize over multiple production years, potentially improving long-term economics for grass-based systems.

Transportation costs disproportionately impact grass silage economics due to its lower energy density. For operations sourcing feedstock beyond 15-20 kilometers, these logistical penalties can eliminate grass silage's production cost advantages. Innovative approaches like mobile pre-treatment technologies that increase energy density before transport may eventually address this limitation, but current commercial systems remain limited.

Subsidies and Support Programs

Government incentives significantly influence feedstock economics across the biogas sector. Many European countries have implemented tiered support systems that provide enhanced payments for environmentally beneficial feedstock choices, including grass from landscape management activities. Germany's Renewable Energy Act revisions have introduced bonus payments for facilities utilizing ecologically advantageous substrates, improving the competitive position of grass silage relative to maize. Similar policy adjustments across the EU reflect growing recognition of biogas's potential role in sustainable landscape management beyond simple energy production.

Carbon pricing mechanisms represent another economic factor increasingly favoring grass silage. As carbon markets mature and prices rise, the improved greenhouse gas performance of grass-based systems translates into tangible financial advantages. Operations in regions with well-developed carbon markets can potentially realize additional revenue streams through carbon credit generation when utilizing low-carbon feedstocks like grass silage from permanent grasslands.

Long-term Financial Sustainability

Forward-looking biogas operators increasingly recognize that long-term financial sustainability requires adapting to evolving regulatory landscapes and consumer preferences. While maize silage currently offers cost advantages in many contexts, facilities designed exclusively around this feedstock face significant adaptation challenges as environmental regulations tighten. Facilities designed with feedstock flexibility from the outset position themselves more advantageously for future market conditions, even if this requires additional initial investment.

Risk diversification provides another compelling economic argument for incorporating grass silage into biogas operations. Facilities reliant on a single feedstock remain vulnerable to crop failures, price volatility, and regulatory changes specific to that substrate. Developing capabilities to efficiently process multiple feedstock types, including grass silage, creates operational resilience that improves long-term business sustainability despite potentially higher short-term costs.

Regional Considerations for Silage Selection

Climate and Growing Conditions

The relative performance of maize versus grass silage varies significantly across climatic regions. Northern European areas with cooler temperatures and higher rainfall naturally favor grass production, where perennial grasses can achieve 80-90% of maize's biomass yields with lower input requirements. In these regions, the productivity gap between feedstocks narrows considerably, making grass silage economically competitive even without policy incentives. Conversely, warmer southern regions with irrigation infrastructure generally maintain maize's productivity advantages, though water scarcity concerns may eventually limit this approach.

Local Agricultural Practices

Existing farming systems and equipment availability significantly impact the feasibility of different silage options. Regions with strong dairy sectors typically have well-established grass silage production capabilities, creating synergies for biogas operations utilizing similar feedstocks. The presence of contractors with specialized equipment for grass harvesting and handling can substantially reduce the investment barriers for biogas operators considering grass silage incorporation. Local agricultural expertise similarly influences implementation success, as grass silage quality depends heavily on proper harvest timing, wilting practices, and ensiling techniques that may require specialized knowledge not required for maize production.

Optimizing Your Biogas Operation

Rather than viewing maize and grass silage as mutually exclusive options, forward-thinking biogas operators increasingly implement strategic combinations that maximize the advantages of each feedstock. This integrated approach offers both operational and environmental benefits that purely maize-based systems cannot achieve. The key lies in thoughtful system design and management practices tailored to specific regional contexts and business objectives.

System optimization begins with realistic assessment of local resource availability, including land characteristics, existing equipment, workforce capabilities, and seasonal constraints. Successful operations typically evolve incrementally, starting with small-scale trials of alternative feedstocks before committing to major system redesigns. This measured approach minimizes disruption risks while building organizational knowledge and capabilities.

Performance monitoring represents another critical optimization element. Comprehensive data collection on feedstock characteristics, digester performance, and economic outcomes enables continuous improvement through evidence-based decision-making. Leading operations implement laboratory testing protocols that provide timely information on silage quality and biogas potential, allowing proactive adjustments to feeding regimes when quality variations occur.

- Conduct small-scale trials before major feedstock transitions

- Implement comprehensive feedstock testing protocols

- Invest in mixing technology for handling diverse materials

- Develop relationships with multiple feedstock suppliers

- Consider seasonal availability in production planning

Best Mixing Ratios for Co-digestion

Co-digestion strategies that combine complementary feedstocks often deliver performance exceeding what either substrate achieves individually. Research has shown that mixtures containing 60-70% maize silage with 30-40% grass silage can maintain 90-95% of pure maize productivity while significantly reducing environmental impact. These blended approaches leverage grass silage's superior protein content and buffering capacity while utilizing maize's higher energy density and consistent digestion characteristics. The optimal ratio depends on the specific characteristics of available materials and digester design, making experimental determination valuable for each operation.

Seasonal adjustment of mixing ratios provides additional optimization opportunities. Many successful operations increase grass silage proportions during spring and early summer when its quality peaks, then transition toward higher maize content during winter months. This approach aligns feedstock utilization with natural production cycles while maintaining relatively stable digester conditions. Gradual transitions between ratio adjustments help prevent biological disruptions that can occur with sudden substrate changes.

Pre-treatment Options to Boost Yields

- Mechanical maceration to increase surface area and digestibility

- Enzymatic treatments targeting lignocellulose structures

- Steam explosion for complex fiber disruption

- Alkali pretreatment to break lignin bonds

- Biological inoculants to enhance initial degradation

Pre-treatment technologies offer promising pathways for improving grass silage performance in biogas systems. These processes address the recalcitrant lignocellulose structures that limit digestion efficiency in fibrous materials. Mechanical pretreatment methods like extrusion and fine grinding have demonstrated yield improvements of 10-25% for grass silage by increasing surface area available for microbial colonization. While these technologies increase processing costs, the productivity gains often justify the investment, particularly for larger operations with economies of scale.

Chemical and biological pre-treatments provide alternative enhancement approaches. Enzymatic additives specifically targeting cellulose and hemicellulose have shown variable but promising results in field trials, with performance improvements ranging from 5-30% depending on grass composition and enzyme formulation. These treatments typically require less capital investment than mechanical systems but add ongoing operational expenses. The economic viability depends on specific facility conditions and local enzyme costs.

Emerging technologies like low-temperature microwave treatment and biological pre-acidification continue expanding the options available for grass silage optimization. These approaches aim to disrupt plant cell structures while minimizing energy inputs compared to conventional pre-treatment methods. While many remain in development stages, commercial implementations have begun demonstrating their practical potential for improving grass silage digestion efficiency without prohibitive cost increases.

Monitoring and Management Systems

Advanced monitoring capabilities have become essential for operations utilizing diverse feedstock strategies. Online gas analysis systems that continuously measure methane concentration, hydrogen content, and other parameters provide early warning of digestion issues before they significantly impact production. These systems allow operators to quickly adjust feeding rates and mixtures when performance metrics indicate suboptimal conditions. The investment in monitoring technology typically pays for itself through improved stability and higher gas yields, particularly for operations with variable feedstock quality.

Feeding automation represents another management advancement that facilitates complex feedstock strategies. Computerized feeding systems can precisely control substrate combinations and loading rates based on predetermined recipes optimized for specific materials. This automation enables sophisticated blending strategies that would be impractical with manual feeding approaches, allowing operations to fully leverage the complementary characteristics of different silage types while maintaining consistent digester conditions.

The Future of Biogas Feedstocks

The biogas industry stands at an evolutionary crossroads as environmental sustainability increasingly influences both policy and market forces. Future developments will likely continue narrowing the performance gap between maize and grass silage through technological innovation, system optimization, and policy frameworks that better account for environmental externalities. Leading operations are already implementing diversified feedstock strategies that maintain productivity while addressing sustainability concerns, establishing templates for wider industry adoption. As carbon constraints intensify across the energy sector, the environmental advantages of grass silage and other alternative feedstocks will translate into stronger economic incentives, accelerating the transition away from maize dominance toward more balanced approaches that better integrate biogas production with sustainable landscape management.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Maize Silage vs Grass Silage Pros and Cons

- What is the average methane yield difference between maize and grass silage?

- How does feedstock choice affect digestate quality and application?

- Can mixed feeding strategies maintain production stability?

- What policy incentives support grass silage adoption?

- How do soil and climate conditions influence optimal feedstock selection?

The biogas industry continues evolving rapidly as technology advances and sustainability priorities shift. These frequently asked questions address common concerns regarding the practical implementation of different silage strategies. While general principles provide useful guidance, local conditions ultimately determine the optimal approach for each specific operation. For more information, check out this alternative to maize silage for biogas.

Successful biogas operations increasingly focus on system integration rather than maximizing single-variable performance metrics. This holistic perspective considers energy output alongside environmental impact, operational stability, and long-term economic viability. As the industry matures, these integrated approaches will likely become standard practice rather than exceptional innovation. For instance, exploring biogas industry growth opportunities in regions like South Korea can provide valuable insights into future trends.

Ongoing research continues expanding our understanding of how different feedstocks perform in various digester configurations and management regimes. Operators benefit from staying connected with research institutions, industry associations, and peer networks that share emerging knowledge and best practices as they develop.

Which silage produces more biogas per hectare?

Maize silage typically produces 30-50% more biogas per hectare than grass silage under comparable conditions. Average yields range from 5,000-9,000 m³ methane per hectare annually for well-managed maize systems, compared to 3,000-6,000 m³ for intensive grass production. However, this productivity gap narrows considerably in northern European conditions where grass performs relatively better and in systems utilizing marginal lands unsuitable for maize cultivation. When accounting for total environmental impact per energy unit produced, grass silage systems often demonstrate superior overall efficiency despite lower raw production numbers.

Can grass silage completely replace maize in biogas plants?

Complete replacement of maize with grass silage presents significant technical and economic challenges for facilities designed around maize characteristics. Digester biology requires gradual adaptation to higher fiber content, potentially causing temporary production declines during transition periods. Most successful conversions implement step-changes of 10-15% substitution rates over extended timeframes to allow biological communities to adjust. Facilities designed specifically for grass silage from inception demonstrate that 100% grass-based production is technically viable, but retrofitting existing operations for complete substitution often remains economically challenging without supportive policy frameworks that monetize the environmental benefits.

What additional costs come with switching from maize to grass silage?

Transitioning from maize to grass silage typically increases costs in several operational areas. Harvesting expenses rise by 20-50% due to multiple cuts and potentially specialized equipment requirements. Transportation costs increase by 15-35% because of lower energy density, requiring more trips for equivalent energy content. Storage infrastructure may require modification to accommodate different material handling characteristics, particularly for facilities using bunker silo systems optimized for maize.

Processing equipment represents another potential cost center, as grass silage often requires more robust handling systems to prevent bridging and flow interruptions. High-fiber materials can accelerate wear on pumps, mixers, and feeding equipment, potentially increasing maintenance expenses and reducing component lifespans. These mechanical challenges become particularly significant when grass silage exceeds 40-50% of the total feedstock mix.

- Higher harvesting frequency and complexity

- Increased transportation requirements per energy unit

- Potential need for specialized handling equipment

- Accelerated wear on mechanical components

- Possible digester performance adjustments during transition

Despite these increased operational costs, the economic equation continues improving for grass silage as environmental regulations tighten and incentive structures evolve to better reflect sustainability impacts. Forward-thinking operators view these transition investments as strategic positioning for future market conditions rather than purely short-term cost increases.

How do seasonal variations affect grass silage biogas production?

Seasonal factors significantly influence grass silage quality and subsequent biogas performance. Spring cuts typically provide the highest protein content and digestibility, generating 15-25% more biogas per ton than late-season harvests. These quality variations require careful management to maintain stable digester performance throughout the year. Successful operations implement strategic storage plans that blend different cutting dates to moderate quality fluctuations. Advanced operators may supplement winter feeding with additives that compensate for seasonal nutrient deficiencies in stored material, maintaining biological stability despite varying substrate characteristics. For more on maintaining digester performance, explore digester cleaning services.

Are there subsidies available for using grass instead of maize for biogas?

Subsidy availability for grass silage varies significantly between countries and even regions within countries. Germany's Renewable Energy Act amendments have introduced specific incentives for environmentally beneficial feedstocks, including bonus payments for landscape maintenance materials and perennial crops. Similar programs exist in Austria, Switzerland, and parts of Scandinavia, though implementation details and payment levels differ considerably. These incentive structures continue evolving as policymakers increasingly recognize biogas's potential role in multifunctional landscape management rather than solely as an energy production technology.

Beyond direct subsidies, carbon credit mechanisms provide additional potential revenue streams for grass-based systems. The improved carbon footprint of grass silage compared to maize creates opportunities for credit generation in regions with functioning carbon markets. While these mechanisms remain under development in many areas, their economic significance will likely increase as carbon pricing matures and becomes more widespread across global economies.

Operators considering feedstock transitions should consult with regional agricultural agencies and renewable energy associations to identify applicable support programs. Many jurisdictions offer transitional assistance specifically targeting diversification away from maize monoculture, including research partnerships, equipment subsidies, and knowledge transfer initiatives that can significantly improve project economics.