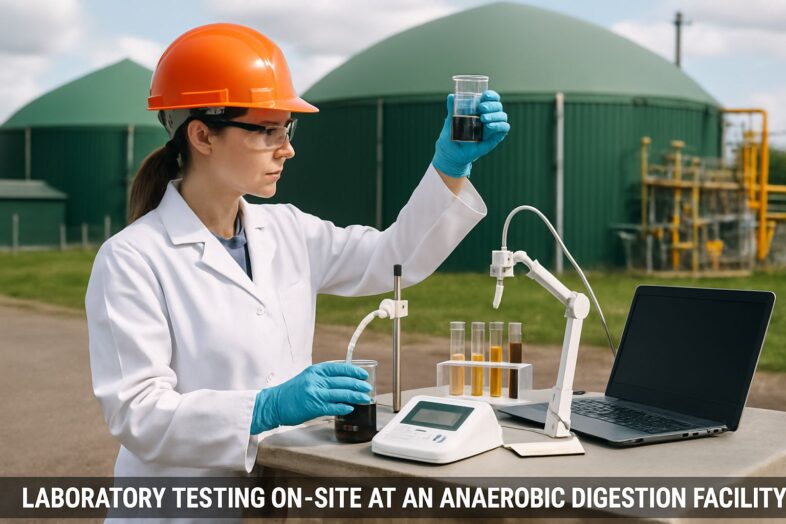

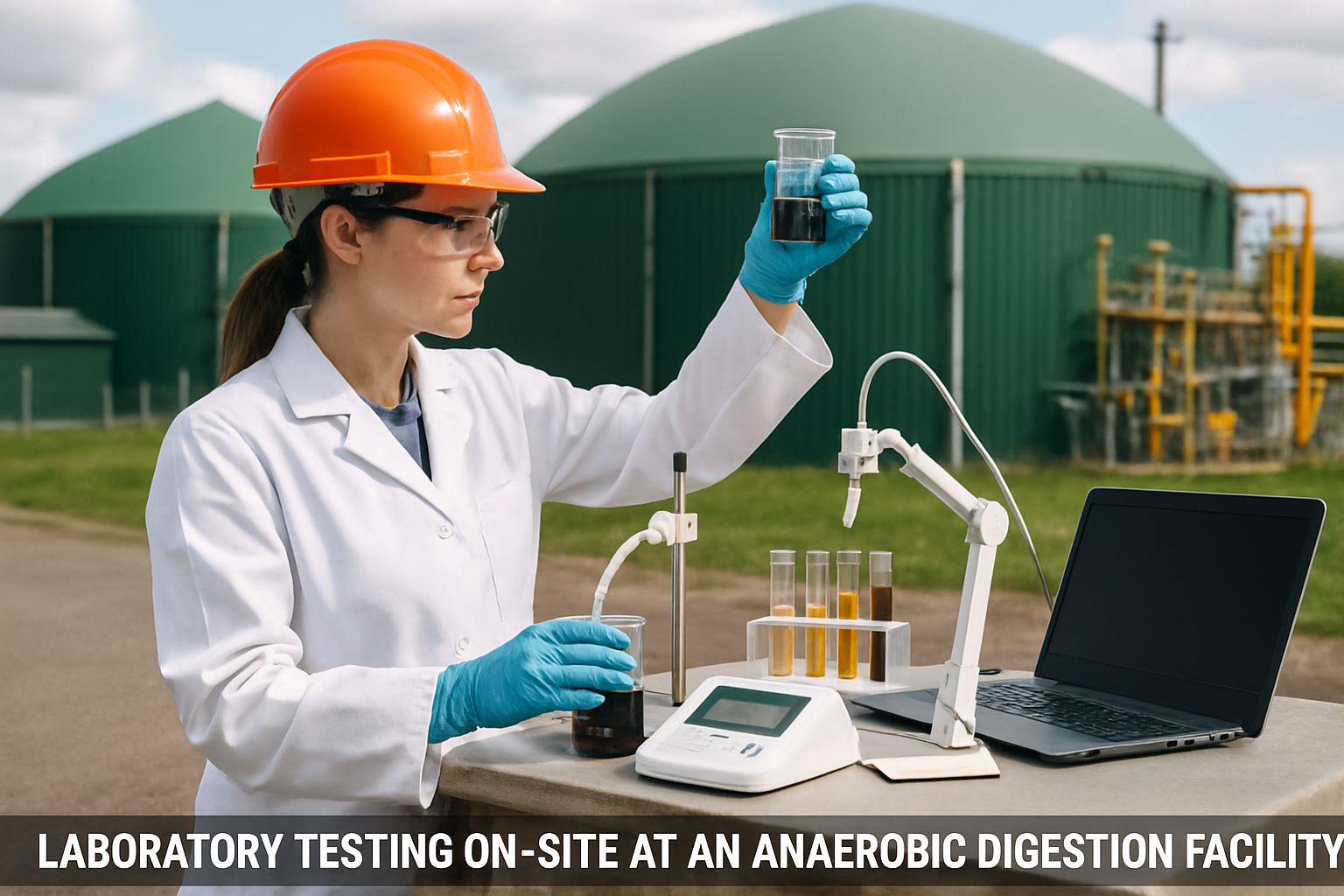

Ammonia inhibition is a major cause of failure in anaerobic digestion facilities (AD) of nitrogen-rich substrates (e.g., manure, food waste), primarily caused by high concentrations of free ammonia NH3. Inhibition, severely reduces methane production. It generally occurs when total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) exceeds 1.5–3 g/L, NH3) being more toxic than ammonium ions NH4. Read on to find out more…

Main Points

- Ammonia inhibition is a major hurdle in anaerobic digestion systems, especially when dealing with nitrogen-rich substrates such as food waste and animal manure.

- The toxicity threshold for ammonia can range from 1500-7000 mg/L, depending on the conditions of the system, with free ammonia being considerably more toxic than ammonium ions.

- The impact of ammonia on biogas production efficiency is heavily influenced by factors such as temperature, pH, and the structure of the microbial community.

- Chemical inhibitors such as metal ions, biochar, and zeolites can effectively counteract ammonia toxicity by binding with ammonia or converting it into less harmful compounds.

- Choosing the correct ammonia control strategy can increase methane yields by 20-40% in affected digesters, making the selection of the right inhibitor essential for renewable energy production.

Ammonia Toxicity: A Silent Threat to Biogas Production

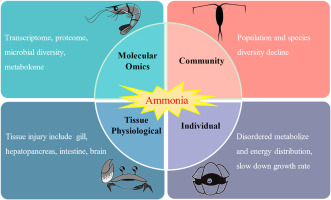

“invertebrates in aquatic environments …” from www.sciencedirect.com and used with no modifications.

Ammonia inhibition is one of the most significant obstacles faced by anaerobic digestion systems across the globe. While ammonia is a natural byproduct of the decomposition of nitrogen-rich organic materials, its accumulation beyond certain levels can wreak havoc on the efficiency of biogas production. This “silent threat” quietly disrupts the microbial communities responsible for converting organic waste into valuable renewable energy, often before operators are even aware of the problem.

Organic waste holds a significant amount of renewable energy potential. If harnessed efficiently, biogas could replace up to 20% of natural gas consumption globally. However, ammonia toxicity is a major limiting factor, reducing methane yields by 30-70% in affected systems. It is critical to understand how ammonia inhibitors work for anyone who operates or designs anaerobic digestion systems, whether for industrial biogas production, agricultural waste management, or municipal treatment facilities.

Understanding the Build-Up of Ammonia During Anaerobic Digestion

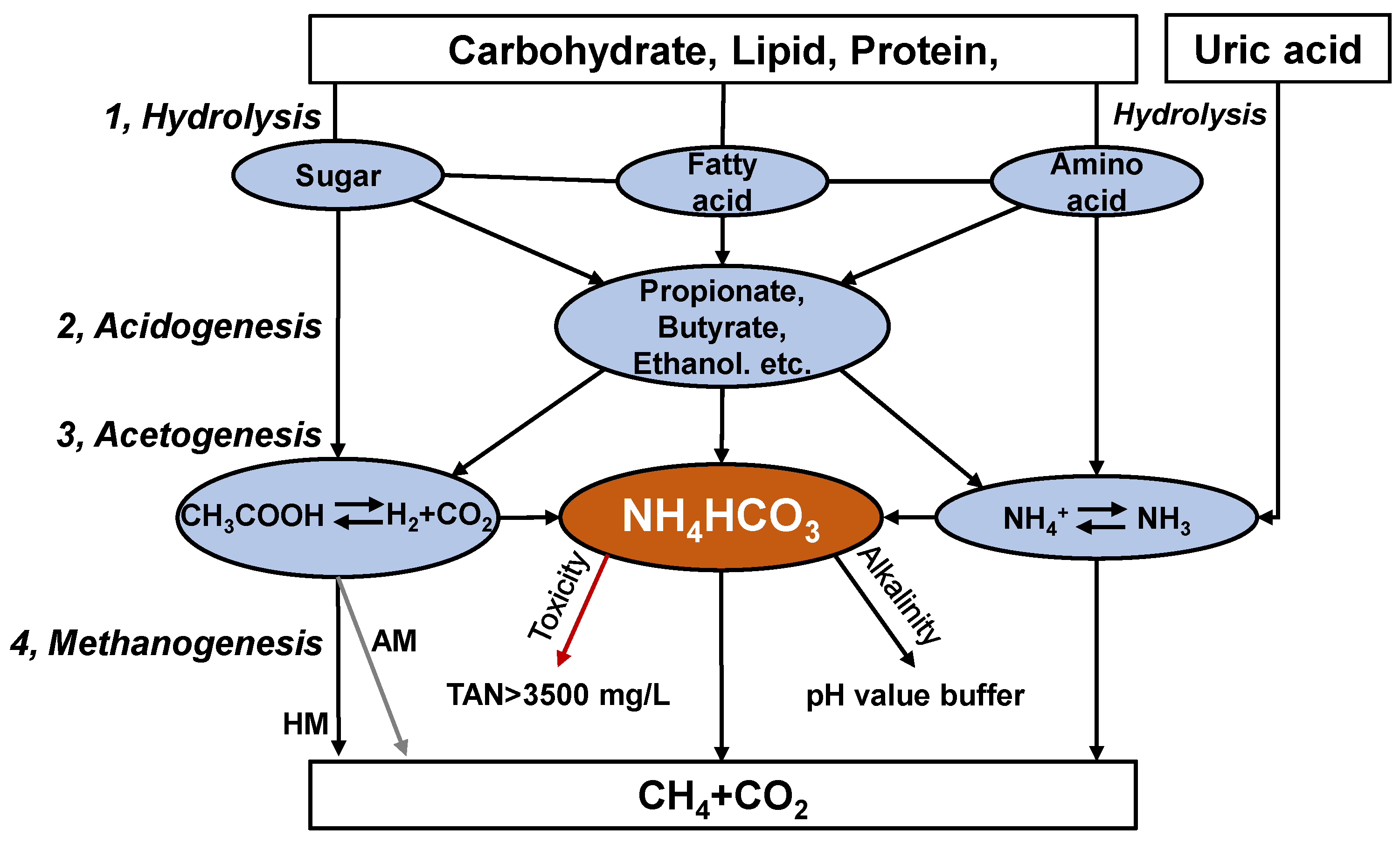

“Ammonia Inhibition | Encyclopedia MDPI” from encyclopedia.pub and used with no modifications.

Contrary to popular belief, ammonia accumulation in digesters isn't a sign of operational malfunction. Instead, it's a natural byproduct of protein degradation during digestion. When nitrogen-rich substrates, such as food waste, slaughterhouse waste, or animal manure, are introduced into the digester, microorganisms break down the proteins and amino acids, which in turn releases ammonia. This process is exacerbated in systems with low carbon-to-nitrogen ratios, where there is not enough carbonaceous material to balance out the nitrogen release.

The breakdown process starts with proteins being turned into amino acids by enzymes outside the cell. These amino acids then go through a process called deamination, where the amino group is removed, creating ammonia. Normally, this ammonia would be absorbed by growing microbial biomass, but if more is produced than can be absorbed, it builds up. The speed at which it builds up is also affected by factors such as the amount of organic matter being processed, the time the water is held back, and the feeding routines.

“Materials high in nitrogen like chicken waste can release ammonia levels over 8,000 mg/L, much higher than the tolerance level of most methane-producing communities. Understanding this biochemical fact is the first step to putting in place effective control strategies.” – International Water Association Anaerobic Digestion Specialist Group

The problem gets worse in continuous digestion systems where regular addition of material adds to the problem, creating a slow buildup that can go from subclinical inhibition to total process failure. Many operators first notice problems only when biogas production has already gone down significantly, making preventative approaches through ammonia inhibitors especially important.

How Methane Production is Affected

![]()

“Effect of ammonia on methane production …” from www.sciencedirect.com and used with no modifications.

When ammonia levels increase beyond what the system can handle, the production of methane is severely impacted in several ways. The first effect that becomes apparent is a decrease in methanogenic activity, where the essential microorganisms that are responsible for the final step in the production of biogas are inhibited. This inhibition causes a domino effect, as the volatile fatty acids (VFAs) that would typically be used by the methanogens start to build up in the system.

Ammonia concentration and methane yield have a direct correlation. When ammonia levels are low (below 200 mg/L), it can actually boost microbial activity by providing a crucial source of nitrogen. When the levels are between 200-1,500 mg/L, most systems function effectively, although they may need to adapt when nearing the top of this range. When the levels exceed 1,500 mg/L, the inhibition becomes more noticeable, with many digesters seeing a 10% decrease in yield for every 500 mg/L increase in ammonia concentration.

| Total Ammonia Nitrogen (mg/L) | Effect on Methane Production | Visible Signs |

|---|---|---|

| 50-200 | Positive (source of nitrogen) | Increased growth, pH stability |

| 200-1,500 | No significant inhibition | Regular operation |

| 1,500-3,000 | Moderate inhibition (10-30%) | Decreasing gas production, VFA accumulation |

| 3,000-5,000 | Severe inhibition (30-70%) | Significant VFA increase, pH instability |

| >5,000 | Potential process failure | Acidification, minimal biogas production |

The economic impact of ammonia inhibition is significant. A typical 1 MW biogas plant with moderate ammonia inhibition could lose €300-500 per day in the value of energy production. Over time, these losses accumulate, making effective ammonia control strategies not only environmentally responsible but also economically necessary for sustainable renewable energy production.

The Impact of Ammonia on the Microbial Environment

Within anaerobic digesters, there is a sensitive equilibrium of co-dependent organisms that operate in sequential metabolic synchrony. Ammonia toxicity doesn't impact all microbes in the same way – it establishes a selective pressure that significantly alters the community structure. This disturbance to the microbial population is what ultimately leads to decreased biogas production efficiency and system instability.

The Most Sensitive Microorganisms: Methanogenic Archaea

When it comes to ammonia toxicity, methanogenic archaea, the specific microorganisms responsible for the last step in methane production, are the most sensitive. These ancient microorganisms, which are different from bacteria in terms of evolution, use unique metabolic pathways that are compromised when ammonia levels increase. Among methanogens, acetoclastic species such as Methanosaeta and Methanosarcina have different vulnerability profiles. For example, Methanosaeta is typically inhibited at concentrations as low as 1,500 mg/L. For more detailed insights, you can explore this research article on the subject.

The reason for this vulnerability is due to the way ammonia can cross cell membranes in its free form (NH₃). When it gets inside the cell, ammonia messes with the proton balance that methanogens need to conserve energy. This is like cutting the power to their ability to produce ATP. The lack of energy stops these organisms from keeping up with important cell functions. This reduces their ability to reproduce and their metabolic activity. If the ammonia environment stays high, it eventually causes the cell to die.

Interestingly, studies have shown that certain methane-producing populations can develop resistance mechanisms when gradually exposed to rising ammonia concentrations. This adaptation seems to involve changes in the composition of the membrane that reduces the permeability of ammonia, changes in the structure of enzymes to maintain function under stress, and changes in the pathways for energy conservation. These adaptations underscore the evolutionary resilience of these ancient organisms, but they require carefully managed periods of acclimatization that many operational systems cannot accommodate.

Change From Acetoclastic to Hydrogenotrophic Routes

The metabolic shift within anaerobic digestion systems is one of the most interesting adaptive responses to ammonia toxicity. Microbial communities undergo a significant transition from acetoclastic to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis routes as ammonia levels rise. This change is a striking example of ecological adaptation, where environmental pressure selects for organisms with a higher ammonia tolerance. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens such as Methanoculleus and Methanobrevibacter species can thrive at ammonia concentrations that would completely inhibit their acetoclastic counterparts.

The carbon flow through the digester is significantly altered by this pathway shift. Instead of directly converting acetate to methane (the acetoclastic pathway), the system increasingly relies on syntrophic acetate oxidation followed by hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. In this alternative route, acetate is first oxidized to hydrogen and carbon dioxide by syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria (SAOB), and hydrogenotrophic methanogens subsequently convert these products to methane. This metabolic detour allows for continued methane production under high ammonia stress, but it typically operates at a lower efficiency, explaining the reduced biogas yields observed in ammonia-inhibited systems.

Studies of digesters under ammonia stress have consistently shown an enrichment of key syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria (SAOB) such as Clostridium ultunense, Syntrophaceticus schinkii, and Tepidanaerobacter acetatoxydans. These specialized bacteria form a close relationship with hydrogenotrophic methanogens and together, they form microbial consortia that can withstand ammonia concentrations in excess of 6,000 mg/L. This natural adaptive response has led to the development of bioaugmentation strategies that deliberately introduce these resilient microbial partnerships to speed up recovery from ammonia inhibition.

How High Ammonia Levels Damage Cells

High levels of ammonia don't just disrupt metabolism, they also cause direct structural and functional damage to microbial cells. Free ammonia (NH₃) can easily penetrate cell membranes because it's uncharged, which makes it an immediate threat to processes inside the cell. Once it's inside, ammonia causes a range of toxic effects: it interferes with potassium transport, increases the energy needed for maintenance, messes with the regulation of intracellular pH, and stops specific enzymatic reactions that are vital for methanogenesis.

Ammonia has a particularly damaging effect on methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR), which is the final enzyme in methanogenesis that is responsible for creating methane. Studies have shown that ammonia directly interferes with the activity of MCR by competing for substrate binding sites and changing the conformation of the protein. This inhibition of the enzyme is why methane production stops well before all the microbes die – the microbes are still alive, but their metabolism is compromised.

Research using electron microscopy has found that ammonia-stressed digesters suffer physical damage to cells. This includes damage to the membrane, unusual cell shapes, and disorganization of the internal structure. These physical changes are linked with a decrease in ATP production and an increase in the energy needed for cell maintenance. This creates an energy shortage that stops microbes from functioning at their best. Ammonia inhibitors that work well prevent these types of cell damage. They do this either by binding to the ammonia before it can get inside the cells or by improving the cells' defenses against ammonia stress.

Ammonia Tolerance Levels in Various Digestion Systems

Ammonia's impact on digestion systems can differ greatly, depending on a variety of operational, environmental, and biological factors. Instead of a one-size-fits-all threshold, operators need to determine tolerance ranges specific to their system. These ranges are influenced by temperature, how the microbial community has adapted, pH levels, and the characteristics of the substrate. Knowing the context of your system is key to applying inhibitor strategies that protect the system without the overuse of chemicals. For more insights, explore biomethane success stories in public transport decarbonization.

Comparing Mesophilic and Thermophilic Temperature Ranges

Temperature plays a significant role in determining ammonia toxicity thresholds. Thermophilic systems, which operate at 50-55°C, are generally more vulnerable than mesophilic systems, which operate at 35-40°C. This temperature effect is due to two interconnected factors: the increased dissociation of ammonium to free ammonia at higher temperatures and the different microbial community structures with varying ammonia tolerance. Although thermophilic digestion has benefits in terms of pathogen reduction and reaction kinetics, its sensitivity to ammonia poses a substantial operational challenge.

Research has shown that mesophilic systems can generally withstand total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) concentrations up to 3,000-5,000 mg/L before they start to experience severe inhibition. On the other hand, thermophilic systems often start to struggle at concentrations as low as 2,000-3,000 mg/L. This difference in tolerance is particularly important when processing nitrogen-rich substrates like poultry litter or food waste. The choice of temperature can determine whether ammonia inhibition becomes a problem. Many facilities that process these challenging feedstocks choose to operate in the mesophilic range. They do this despite the kinetic advantages of thermophilic operation, specifically to reduce the risk of ammonia toxicity.

Microbial communities in mesophilic digesters usually have more species diversity, which provides more metabolic pathways and increases resilience against ammonia stress. This advantage in community structure, along with lower free ammonia fractions at lower temperatures, is why mesophilic operations often remain stable at ammonia concentrations that would cause thermophilic systems to fail. For those who operate thermophilic systems, this vulnerability makes it especially important to choose the right ammonia inhibitors to maintain process stability.

How Free Ammonia Differs from Total Ammonia Nitrogen

One of the most important things to understand about ammonia toxicity is the difference between free ammonia (NH₃) and ammonium ion (NH₄⁺). These two forms are in equilibrium, and their relative proportions are mainly determined by pH and temperature. Free ammonia is uncharged and lipophilic, so it can easily cross cell membranes. It can cause toxic effects at concentrations as low as 80-150 mg/L. On the other hand, the charged ammonium ion can't easily penetrate cell membranes. It mainly causes toxicity through indirect mechanisms, and it usually takes much higher concentrations (typically above 1,500 mg/L) to cause toxicity.

“The balance between free ammonia and ammonium ion follows a predictable equilibrium relationship. At pH 7 and 35°C, only about 1% of total ammonia exists as free ammonia. However, at pH 8 under the same temperature, this fraction increases to approximately 10%, potentially pushing a previously stable system into toxicity without any change in total ammonia concentration.”

This relationship between free ammonia fraction and pH explains why digesters can suddenly experience inhibition following seemingly minor pH increases. Many effective ammonia management strategies target this equilibrium relationship, using pH manipulation to shift ammonia toward the less toxic ammonium form. However, this approach requires careful balance, as excessive pH reduction can inhibit methanogenesis through other mechanisms. The most effective ammonia inhibitors operate by directly binding free ammonia or facilitating its conversion to less harmful forms without requiring significant pH adjustments.

How pH Affects Ammonia's Toxicity

The pH value is not only a significant factor in ammonia's toxicity, but it also serves as a potential control parameter. As the pH rises, the equilibrium between the ammonium ion and free ammonia dramatically shifts towards the more toxic free form. This relationship creates a difficult operational problem, as the optimal pH range for methanogenic activity (7.0-8.2) coincides with conditions where free ammonia fractions increase significantly. At a pH of 7.0, only about 0.5-1% of total ammonia exists as free ammonia, but this fraction increases to 5-10% at a pH of 8.0, potentially multiplying toxicity effects without any change in total ammonia concentration.

There is a complex interaction between pH and ammonia toxicity in digesters. When ammonia initially inhibits the digester, methane production often decreases, leading to a buildup of volatile fatty acids. These acids then lower the pH of the system, which can temporarily relieve ammonia toxicity by shifting towards ammonium ions. However, this decrease in pH eventually inhibits methanogenesis due to acid toxicity, creating an unstable system that oscillates and eventually leads to the failure of the digester. Effective ammonia inhibitors can break this destructive cycle by addressing the root cause of ammonia toxicity while keeping the pH within the optimal range for methanogenic activity.

There are many operational strategies that intentionally keep pH at the lower end of the acceptable range (7.0-7.5) in digesters processing nitrogen-rich substrates to minimize the formation of free ammonia. However, this approach sacrifices some methanogenic efficiency and provides limited protection when total ammonia levels continue to rise. More sophisticated approaches combine chemical inhibitors with careful pH management, using compounds that specifically target free ammonia while maintaining optimal conditions for the overall microbial community.

6 Chemical Inhibitors That Can Help You Fight Ammonia Toxicity

Chemical methods to reduce ammonia toxicity are some of the fastest and most effective solutions that biogas operators have at their disposal. These inhibitors work in a variety of ways, from directly binding to ammonia to precipitation reactions that remove ammonia from the solution. The choice of the right chemical inhibitors depends on the characteristics of the system, the concentration of ammonia, economic factors, and whether they are compatible with downstream processes. When used correctly, these chemical methods can restore between 70% and 90% of the potential for methane production in systems that are severely inhibited, in a matter of days to weeks.

1. The Role of Metal Ion Additives (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺)

When it comes to reducing the impact of ammonia, metal cations, particularly magnesium (Mg²⁺) and calcium (Ca²⁺), play a crucial role. They work in several ways. For example, these divalent cations can form complexes with ammonia. They can also help ammonia precipitate as struvite (MgNH₄PO₄·6H₂O) or similar compounds when phosphate is present. But their role doesn't end there. These metal ions can also increase microbial tolerance to ammonia stress. They do this by stabilizing cell membranes and enhancing ion exchange processes. This helps to maintain cellular homeostasis under toxic conditions. For more insights, explore how engineers at biogas facilities manage similar challenges.

2. The Power of Biochar and Activated Carbon

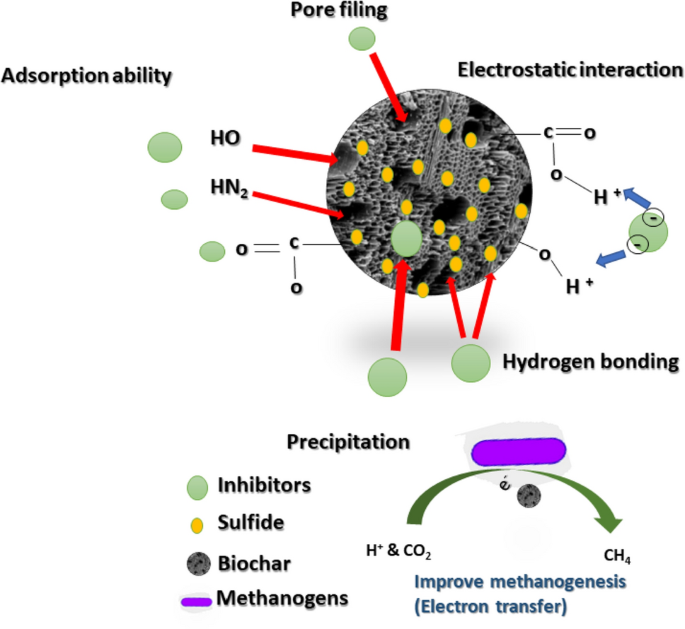

“Biochar for agronomy, animal farming …” from link.springer.com and used with no modifications.

Biochar and activated carbon are two of the most effective adsorptive materials available. They can significantly reduce ammonia toxicity through both physical and chemical means. These carbon-based materials have large networks of micropores that physically capture ammonia molecules. Additionally, their surface functional groups form chemical bonds with nitrogen compounds. Studies show that adding 10-15 g/L of biochar can reduce free ammonia concentrations by 30-50% in heavily inhibited digesters. At the same time, they also improve microbial attachment surfaces and nutrient exchange, as seen in biogas plant operations.

One of the significant benefits of biochar is that it can be produced from digestion byproducts. This process creates a circular solution where digestate is pyrolyzed to make the material that improves digester performance. This method turns what would be a waste product into a valuable operational input. Also, biochar shows remarkable selectivity, preferentially binding ammonia while having minimal impact on beneficial nutrients. This feature makes it especially suitable for systems where maintaining nutrient balance is crucial.

Usually, the process is carried out by directly adding it to the digestion tank or by integrating it into external columns where the digestate is circulated. Columns offer more controlled adsorption and simpler replacement of saturated material, while direct addition provides simplicity and continuous contact. Although regeneration processes can prolong the life of biochar, many operators simply integrate spent biochar into land application programs. Here, its ammonia content provides value as a fertilizer, while its carbon structure improves soil properties.

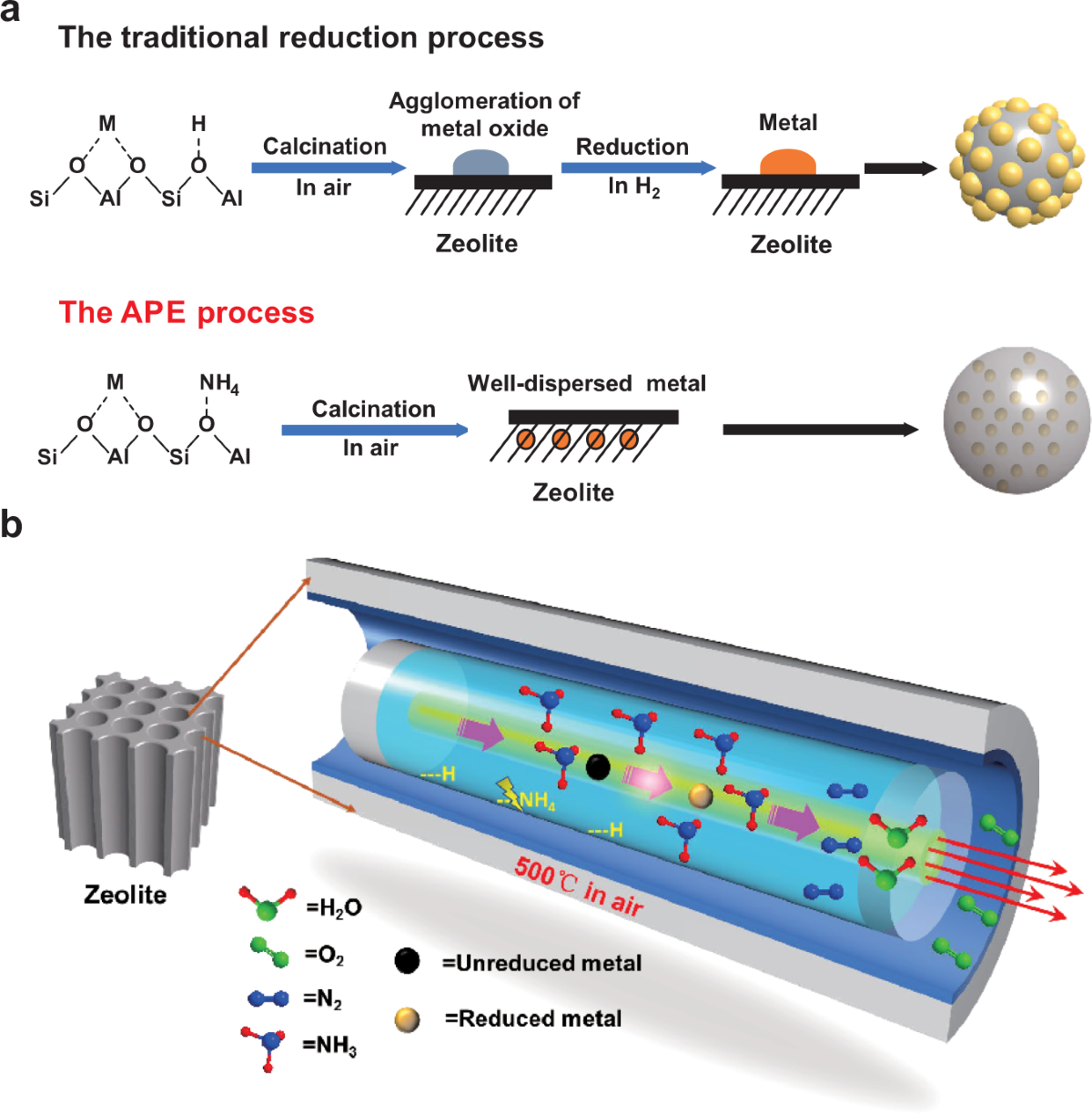

3. Zeolites and Natural Clay Materials

“Ammonia pools in zeolites for direct …” from www.nature.com and used with no modifications.

Natural zeolites, especially clinoptilolite, are some of the most commonly used ammonia inhibitors because they have a high ion-exchange capacity and are relatively inexpensive. These aluminosilicate minerals have regular microporous structures with a high specific surface area and a strong affinity for ammonium ions. When they are added to digesters at concentrations of 2-5% (w/v), zeolites can reduce free ammonia by 40-70% and at the same time provide alkalinity buffering that stabilizes the pH of the system.

The ion-exchange process involves swapping ammonium ions (NH₄⁺) with naturally occurring cations (usually Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, or Mg²⁺) within the zeolite structure. This exchange can be reversed and is dependent on concentration, forming a dynamic buffer that absorbs ammonia during periods of peak production and potentially releases captured ammonia when concentrations decrease. Modified zeolites, which have been treated with acids or surfactants to increase their exchange capacity, have proven to be even more effective, reducing the required dosages by 30-50% compared to natural materials.

Clay materials like bentonite and montmorillonite provide similar benefits but with different binding mechanisms. These layered silicates intercalate ammonium between their structural sheets while also providing a large surface area for microbial attachment. The combination of ammonia binding and biofilm support creates synergistic benefits, with studies showing methane production increases of 25-40% following clay addition to inhibited systems. For agricultural biogas operations, the compatibility of these natural materials with land application of digestate is a particular advantage, as they contribute to positive soil conditioning properties when the digestion cycle is complete.

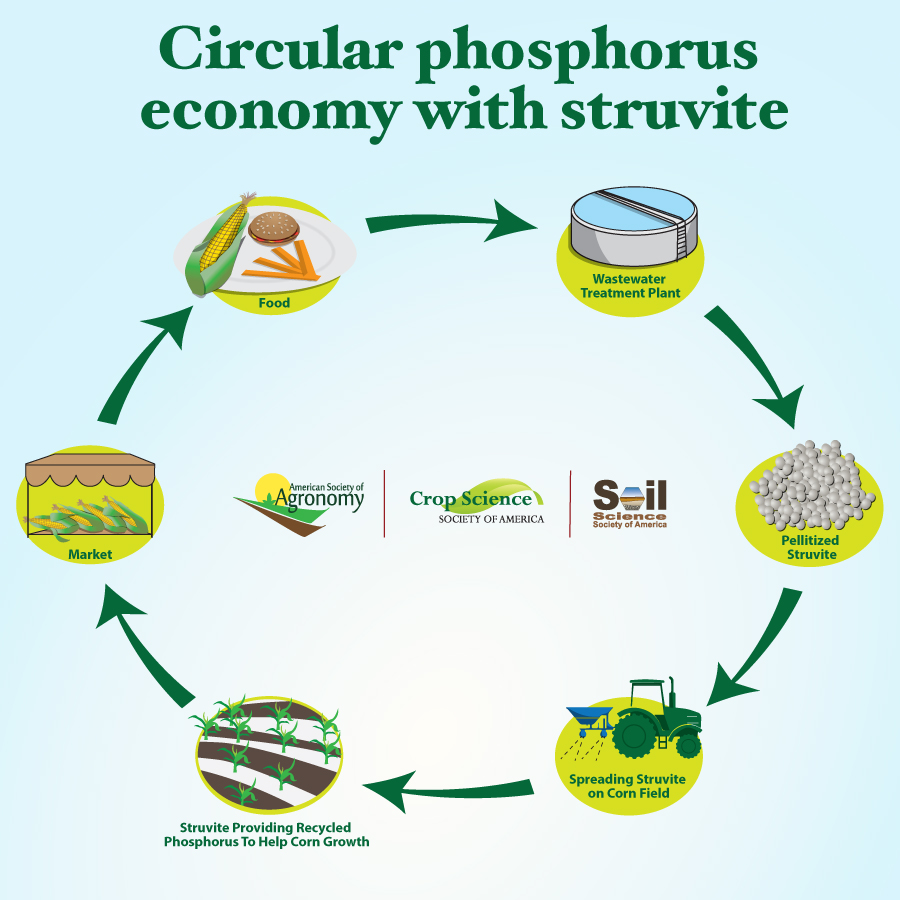

4. The Formation of Phosphorite and Struvite

“What is struvite and how is it used …” from soilsmatter.wordpress.com and used with no modifications.

One of the most successful chemical methods for controlling ammonia is the deliberate precipitation of ammonia through the regulated formation of struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate, MgNH₄PO₄·6H₂O). By adding sources of phosphate and magnesium in a controlled pH environment, operators can transform soluble ammonia into a crystalline form that is insoluble, effectively removing it from the active digestion process. This process usually removes 80-90% of the dissolved ammonia and produces a high-value slow-release fertilizer byproduct that can be sold separately.

Phosphorite, a phosphate-rich mineral that occurs naturally, is an affordable source of phosphorus for this process, although synthetic phosphates such as disodium phosphate allow for more accurate control. The reaction requires meticulous pH management, usually between 8.0 and 9.0, which necessitates a temporary pH adjustment followed by a return to optimal digestion conditions. Modern versions frequently employ sidestream precipitation reactors that treat a portion of the digestate on a continuous basis, gradually lowering ammonia levels without interfering with the main digestion process.

Struvite precipitation is not only beneficial for ammonia control, but it also offers more operational benefits. These include less pipe scaling, better dewatering features, and phosphorus recovery. This is important because phosphorus is a valuable and limited resource. The crystallization process also removes heavy metals through co-precipitation, which could improve digestate quality. Although it requires a moderate capital investment to implement, the operational benefits and potential revenue from struvite fertilizer often make it economically favorable. This is especially true for medium to large-scale operations processing nitrogen-rich feedstocks.

5. Ion Exchange Resins

“Anion Exchange Resins as a Source of …” from pubs.acs.org and used with no modifications.

Artificial ion exchange resins are more effective in removing ammonia than natural materials like zeolites. These are specially designed polymers that can bind ammonium ions with high capacity and selectivity. Sulfonic acid group-containing strong acid cation exchange resins are particularly effective, capable of reducing total ammonia nitrogen by 85-95% when used in well-designed contactors.

Unlike adsorption materials that eventually become saturated, ion exchange resins can be regenerated hundreds of times using salt solutions, acids, or bases to displace the ammonia that has been captured. This makes them economically viable despite their higher initial costs. Most implementation approaches use packed-bed columns to treat digestate sidestreams rather than adding them directly to digestion tanks. This allows for controlled contact time and simplified regeneration. Advanced systems include multiple columns that operate in sequence to ensure continuous treatment capability during regeneration cycles.

New advancements have led to the development of specialty resins with functional groups that are specifically designed for ammonia selectivity in the complex ionic environment of digestate. These materials can still function effectively even in high-salt conditions that would typically compromise conventional resins, although they do come at a higher cost. For large-scale operations that are dealing with serious ammonia challenges, the operational reliability and exceptional removal efficiency of these engineered solutions often justify their higher implementation costs, especially when the alternative is process failure or significant biogas production loss.

“Ion-exchange resin – Wikipedia” from en.wikipedia.org and used with no modifications.

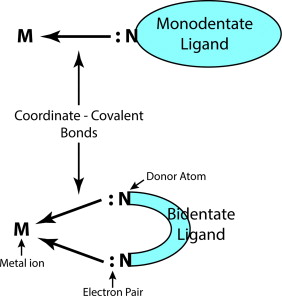

6. Chelating Compounds

Chelating compounds are a complex chemical solution to ammonia inhibition.

“Chelation – an overview | ScienceDirect …” from www.sciencedirect.com and used with no modifications.

They create stable complexes with ammonium ions, reducing their bioavailability without necessarily removing them from the solution. These specific molecules contain multiple binding sites that “trap” ammonia, preventing it from interacting with microbial cells while maintaining the nitrogen balance of the system. EDTA, citric acid derivatives, and specialized polymeric chelators have shown significant effectiveness, especially in high-value applications where the stability of the process justifies their high cost.

Unlike precipitation or adsorption methods, the mechanism is fundamentally different because chelated ammonia stays in solution but in a form that cell membranes cannot easily penetrate or disrupt metabolic processes. This property makes chelators especially appropriate for systems where nitrogen retention is desirable for downstream processes or where water conservation prevents dilution strategies. Modern formulations combine multiple chelating agents with synergistic effects, achieving 30-60% reductions in effective ammonia toxicity without altering total nitrogen content.

Usually, the process involves the continuous addition of a small dose in proportion to the feed rate. This creates a steady state in which new ammonia is continuously chelated as it is produced. Although the cost of materials is higher than for simpler inhibition methods, the precision and control offered by chelation make it a valuable tool for systems that process variable feedstocks. In these systems, spikes in ammonia could otherwise disrupt the process. For large-scale industrial operations where the reliability of the process is of paramount importance, chelating compounds are often a cost-effective way to prevent catastrophic inhibition events.

Natural Methods to Combat Ammonia Inhibition

Chemical inhibitors are a quick fix for ammonia toxicity, but biological methods offer a more sustainable solution for the long haul by making the system more resilient. These methods use natural microbial adaptation mechanisms, community engineering, and substrate management to create digester ecosystems that can survive even when ammonia levels are high. Biological methods usually take longer to implement, but they often provide more stable performance and require fewer chemical inputs once they are up and running.

How Microbial Communities Acclimate

Microbial communities naturally acclimate to ammonia toxicity by gradually exposing themselves to increasing concentrations, which is how they develop resistance. This adaptation involves a variety of mechanisms, such as changes in the composition of the cell membrane, the expression of specialized ammonia transport proteins, and the selection of naturally resistant microbial strains. If done correctly, acclimation can create communities that can maintain efficient methane production at ammonia concentrations 2-3 times higher than those that would inhibit non-acclimated populations.

The acclimation protocol usually starts with moderate ammonia levels (1,000-1,500 mg/L) and gradually increases the levels by 200-500 mg/L over periods of 2-3 hydraulic retention times at each level. This allows time for physiological adaptation within existing organisms and community succession towards more ammonia-tolerant species. Although it requires patience and careful monitoring, successful acclimation programs have developed communities that can operate stably at total ammonia nitrogen levels exceeding 5,000 mg/L in mesophilic systems and 3,000 mg/L in thermophilic environments.

Research into adapted communities at the molecular level has uncovered some intriguing mechanisms of adaptation. These include the enrichment of syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria, which bypass the metabolic pathways that are most sensitive to ammonia, and the selection of specialized hydrogenotrophic methanogens, which have a naturally higher tolerance to ammonia. These shifts in the community fundamentally change the flow of carbon through the digestion system. They allow methane production to continue via alternative routes when the usual routes become inhibited. For operators who consistently process feedstocks rich in nitrogen, investing in the right acclimation protocols often provides the most sustainable long-term solution to the challenges posed by ammonia. For more insights into the biogas industry, check out The American Biogas Council.

Enhancing with Ammonia-Resistant Species

Enhancing the natural adaptation process by intentionally introducing ammonia-resistant microbial groups into struggling digesters is known as bioaugmentation. This strategy essentially provides a ready-made solution to the ammonia problem by inoculating pre-adapted microbial specialists capable of maintaining methanogenic activity under high ammonia stress. Carefully selected bioaugmentation cultures typically include syntrophic acetate oxidizers (like Clostridium ultunense and Tepidanaerobacter acetatoxydans) paired with hydrogenotrophic methanogens (such as Methanoculleus species) known for their exceptional ammonia tolerance.

There are different ways to carry out the process, from adding a large volume of inoculations (10-15% of reactor volume) all at once, to adding smaller amounts over several weeks. This is often done in conjunction with reduced feeding to give the new organisms a chance to get established. The most successful methods involve a combination of bioaugmentation and careful control of operational parameters that favor the new species. This includes optimizing the temperature, supplementing with trace elements, and using the right organic loading rates. More and more commercial bioaugmentation products are including specialized carrier materials that protect the new microorganisms during the establishment phase. This has been shown to improve success rates in systems that are heavily inhibited.

Studies have shown that if bioaugmentation is done correctly, it can restore between 50-80% of methane production capacity within 2-4 weeks in severely inhibited digesters. This is in comparison to recovery periods of 2-3 months for natural adaptation. While it does require an initial investment in specialized cultures, the accelerated recovery timeline often provides a strong economic return by minimizing the loss of energy production. For operators who are dealing with acute ammonia toxicity events, bioaugmentation provides a quick intervention option that complements longer-term chemical or process management strategies.

Co-digestion as a Strategy to Maintain Carbon-Nitrogen Balance

One preventative approach to ammonia inhibition is strategic co-digestion, which involves diluting nitrogen-rich substrates with carbon-rich materials. This method of substrate management aims to keep the carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio within the optimal range of 20-30:1. This prevents excessive accumulation of ammonia while ensuring there is enough nitrogen for microbial growth. Common carbon-rich co-substrates include crop residues, paper waste, cardboard, and lignocellulosic materials. These materials provide plenty of carbon and contribute minimal nitrogen.

Co-digestion strategies that are well-designed offer more than just simple dilution effects. They create synergistic benefits by improving nutrient balance, enhancing hydrolysis kinetics, and diversifying microbial substrates. The perfect co-digestion regime balances several operational objectives, such as controlling ammonia, producing biogas, ensuring the quality of digestate, and maintaining system stability. Operators who are sophisticated develop dynamic mixing ratios that adjust to the seasonal variations in the composition of the substrate. This allows them to maintain consistent performance despite the fluctuating characteristics of the input.

It’s crucial to thoroughly understand the possible co-substrates before implementing them. You’ll also need to accurately calculate mixing ratios and potentially modify feeding systems to handle a variety of materials. While co-digestion requires more complex logistics than single-substrate digestion, it often provides significant performance enhancements beyond ammonia control. These enhancements can include a 15-40% increase in specific methane yield, improved digestate dewaterability, and reduced hydrogen sulfide production. For agricultural operations, strategic co-digestion of locally available biomass streams offers both ammonia management and enhanced energy production with minimal additional investment.

Changes in Processes That Minimize Ammonia Impact

Engineering solutions to ammonia inhibition tackle the issue through state-of-the-art system designs and operational strategies that fundamentally change how digesters deal with nitrogen-rich substrates. These methods modify crucial process parameters such as temperature profiles, physical configuration, and hydraulic patterns to minimize ammonia toxicity without the need for constant chemical intervention. While these structural solutions often require capital investment, they usually provide long-lasting performance improvements with fewer ongoing operational requirements, as seen in custom-built chopper pumps and industrial mixers.

Two-Stage Digestion Systems

Two-stage digestion is an architectural approach to overcoming ammonia problems by physically separating the acidogenic and methanogenic stages of anaerobic digestion. This layout places the hydrolysis and acidification steps in a first-stage reactor that is designed to rapidly produce acid, followed by a second-stage reactor that is specifically designed for methanogenesis under controlled conditions. The separation creates unique microbial environments that can be independently optimized, allowing for targeted ammonia management strategies at each stage.

The primary reactor normally runs at a shorter hydraulic retention period (1-3 days), a lower pH (5.5-6.0), and occasionally a higher temperature to maximize hydrolysis and acidogenesis while reducing methanogenic activity. This environment is intentionally designed to produce volatile fatty acids and release ammonia from protein breakdown. The secondary reactor then receives this pre-acidified material under conditions that are ideal for methanogenic activity, with potential ammonia control measures specifically aimed at protecting the sensitive methanogens rather than the entire microbial community.

Research has shown that two-phase systems are capable of maintaining stable methane production at total ammonia nitrogen levels that are 30-50% higher than conventional single-stage systems processing the same substrates. This increased tolerance is due to several factors, including the acidic conditions in the first phase which shift ammonia toward the less toxic ammonium form, the physical separation which allows for targeted ammonia removal between phases, and the specialized methanogenic community in the second phase which has developed increased ammonia tolerance. Despite requiring additional capital investment and operational complexity, two-phase configurations often represent the most effective solution for consistently processing highly nitrogenous materials such as poultry litter, slaughterhouse waste, or concentrated food processing residues.

Methods for Controlling Temperature and pH

Advanced methods for controlling temperature and pH use the chemical balance between free ammonia and ammonium to reduce toxicity without sacrificing process efficiency. Temperature has a direct effect on this balance, with lower temperatures shifting toward the less toxic ammonium form. It also affects the rates of microbial activity and the composition of the community. Operators who process substrates rich in nitrogen are increasingly using approaches that are phased according to temperature. These combine thermophilic pre-treatment for reducing pathogens and enhancing hydrolysis with mesophilic methanogenesis to improve tolerance of ammonia.

Another effective method of control is through pH manipulation. Even minor reductions in pH can greatly reduce the amount of free ammonia. Sophisticated control systems keep the pH at the lower end of the optimum range for methanogenesis (about 7.0-7.2), which maximizes methanogenic activity while minimizing the formation of free ammonia. Some cutting-edge operations use dynamic pH control, which allows for minor natural pH fluctuations during periods of low activity, but tightens control when ammonia concentrations near critical levels. This creates an adaptive response to changes in inhibition pressure.

The most successful methods combine temperature and pH control with continuous monitoring of important process indicators such as volatile fatty acid concentrations, alkalinity ratios, and biogas composition. These integrated control systems can identify early indicators of ammonia inhibition and make preventative adjustments before significant performance decline occurs. While these methods require sophisticated instruments and control algorithms, they often provide the most stable long-term performance for systems that process variable nitrogen-rich feedstocks where ammonia concentrations fluctuate unpredictably.

Watering Down and Preparing Feedstock

Watering down is a simple strategy for managing ammonia by reducing the concentration below the levels that cause problems, but concerns about saving water are making it less and less common. These days, the focus is on watering down only where needed, using water from the process rather than adding fresh water. This creates systems that recirculate internally, which is better for the environment and still controls ammonia. These systems usually water down and feed in carefully timed amounts, spreading out the feedstock that is high in nitrogen over time to avoid sudden increases in concentration that could set off a chain reaction of problems.

More advanced solutions are offered by feedstock pre-treatment technologies, which selectively remove or bind nitrogen before the materials enter the main digestion system. Physical processes such as solid-liquid separation, ammonia stripping, and membrane filtration can remove 30-60% of potential ammonia from high-nitrogen substrates before digestion. Biological pre-treatments use aerobic microbial processes to convert organic nitrogen to biomass instead of ammonia, providing another approach. This is particularly suitable for protein-rich industrial byproducts, where conventional digestion would generate prohibitively high ammonia concentrations.

There are other intervention categories that use chemical pre-treatments with acids, specific binding agents, or precipitating compounds to create stable nitrogen forms that release more slowly during digestion. These approaches often prove to be cost-effective for materials that would otherwise require too much inhibitor addition or cause process instability, even though they require additional processing steps. The best approach depends on the specific characteristics of the substrate, the infrastructure available, water constraints, and operational objectives. Many facilities implement hybrid strategies that combine several ammonia management techniques to achieve optimal performance.

Ammonia Removal Techniques

Ammonia stripping is a highly efficient physical-chemical method for removing ammonia from digestion systems, especially when used as a sidestream treatment process. This technique uses the volatility of ammonia by raising the pH (usually to 9-10) and temperature and adding a stripping gas (air or biogas) that carries the volatilized ammonia out of the solution. Contemporary applications capture this stripped ammonia in acid scrubbers, transforming it into valuable ammonium sulfate fertilizer and permanently eliminating nitrogen from the digestion system.

Highly developed stripping systems can remove 80-98% of ammonia, depending on the conditions, which effectively solves even the most severe ammonia inhibition situations. Most commonly, this process is used as a sidestream treatment. This means that a portion of the digestate is continuously removed, treated to remove ammonia, and then returned to the main digestion vessel. This gradually reduces the total amount of ammonia in the system while keeping the hydraulic balance. This method allows for precise control over the rate of ammonia removal without disrupting the main digestion process or needing to completely empty the system. For more on the industry, explore where the biogas industry connects, learns, and grows.

Ammonia stripping, though requiring a modest initial investment, offers attractive economics through several value streams: increased biogas production due to relieved inhibition, the production of marketable fertilizer from captured ammonia, and potential environmental credits from reduced nitrogen discharge. For large-scale operations that consistently process nitrogen-rich feedstocks, integrated stripping systems often offer the most sustainable long-term solution for managing ammonia, while also contributing positively to the overall economics and environmental performance of the facility.

Real-World Success: Case Studies of Effective Ammonia Management

Looking at successful applications of ammonia control strategies can give us useful insights into the practical application challenges and what kind of performance we can realistically expect. These case studies show us how theoretical approaches work in the real world, across different types of facilities, scales, and geographical contexts. While the specific solutions depend on local conditions, the availability of feedstock, and economic constraints, there are certain common factors for success that we can see across multiple applications. These can provide guidance for facilities that are developing their own approaches to managing ammonia.

Recovering a Food Waste Digester After Ammonia Overload

After accidentally loading a commercial food waste digestion facility in the northeastern United States with nitrogen-rich slaughterhouse waste, ammonia concentrations spiked to 6,500 mg/L and methane production dropped by 78% within 48 hours, leading to a severe ammonia inhibition. To combat this, the facility implemented a comprehensive recovery strategy that included several ammonia control methods: the immediate addition of zeolite (5% w/v) to bind free ammonia, pH reduction from 7.8 to 7.2 using controlled carbon dioxide sparging, and bioaugmentation with a specialized ammonia-tolerant consortium. This multi-pronged intervention resulted in a 50% recovery of methane production within a week and a 90% recovery within 25 days, saving an estimated $175,000 in potential lost energy revenue.

Animal Waste Processing Plants

In Wisconsin, a group of dairy manure digesters used struvite precipitation as their main method of ammonia control. This helped them to solve ongoing inhibition problems and create valuable fertilizer at the same time. They used a sidestream treatment system where they processed about 20% of the digester volume daily in special precipitation reactors. These reactors mixed magnesium oxide and phosphoric acid under controlled pH conditions. This process removed 65-75% of total ammonia nitrogen and produced 1.2 tons of crystalline struvite fertilizer for every million gallons of manure they processed. Besides controlling ammonia, the plants also reported several operational benefits. These included less pipe scaling, better digestate dewatering performance, and a 22% average increase in specific methane yield. This meant that they recouped the cost of implementing the system in just 3.5 years through the combined income from energy and fertilizer.

City Sewage Treatment Plants

A city sewage treatment plant in Denmark was having trouble with ammonia inhibition in their digestion of mixed primary and waste activated sludge. They decided to try a new approach that would increase the temperature in phases, and it worked wonders. Instead of keeping all the digesters at the usual mesophilic temperatures (35-38°C), they rejigged their system to include a thermophilic pre-treatment stage (55°C with 1.5-day retention) before the mesophilic digestion (37°C with 15-day retention). This way, they could still get rid of pathogens with the high-temperature treatment while reducing the amount of time the main digestion phase was exposed to ammonia toxicity. The results were impressive. The volatile solids destruction went up by 14%, biogas production increased by 23%, and polymer consumption for dewatering went down by 17%. This led to significant operational savings and only required a small capital investment to modify the control system.

From these success stories, we can draw a few important conclusions about managing ammonia effectively. First, using multiple mechanisms together in an integrated approach generally works better than relying on a single technology. Second, the ability to adapt your strategy to changing conditions can significantly improve the results. Finally, when you control ammonia properly, you can prevent inhibition and often improve many different aspects of digestion performance at the same time.

Understanding the Economic Impact of Various Inhibitor Methods

Ultimately, the economic implications are what dictate the widespread use of ammonia control strategies, regardless of how technically effective they may be. A thorough cost-benefit analysis should take into account not only the direct costs of implementation, but also the benefits of improved performance, operational savings, valuable byproducts, and the costs avoided by preventing system failures. This multifaceted economic evaluation shows that while some ammonia management strategies may require a significant investment, the returns can often far outweigh the costs when all sources of value are properly taken into account.

Initial Costs vs. Ongoing Costs

Ammonia control strategies can have a wide range of financial profiles, from low upfront costs but high operating costs like continuous chemical dosing, to high upfront costs but low operating costs such as advanced stripping systems. Chemical inhibitors like zeolites, biochar, and metal salts usually require a small initial investment (mainly for storage and dosing equipment) but have ongoing material costs that are proportional to the amount of ammonia. On the other hand, physical-chemical systems like stripping columns, membrane contactors, and precipitation reactors require a large initial investment ($250,000-$2,000,000 depending on the size) but usually have a lower long-term cost per unit of ammonia removed once the initial investment has been paid off.

Increased Energy Output From Correct Inhibitor Application

| Ammonia Management Approach | Usual Increase in Methane Output | Cost Range for Implementation | Payback Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolite Addition | 15-30% | $0.5-2.0/ton substrate | 0.5-2 years |

| Biochar/Activated Carbon | 20-40% | $1.0-3.5/ton substrate | 1-3 years |

| Struvite Precipitation | 25-45% | $500K-2M capital + $0.3-1.0/ton operational | 2-5 years |

| Ammonia Stripping | 30-60% | $750K-3M capital + $0.4-1.5/ton operational | 3-7 years |

| Two-Phase Digestion | 35-55% | $1M-4M capital + $0.2-0.8/ton operational | 4-8 years |

The primary economic incentive for applying ammonia control in most biogas systems is the increase in energy production. Facilities that have moderate to severe ammonia inhibition typically experience a 20-60% increase in methane output following a successful intervention, which directly translates to a proportional increase in energy production and revenue. For a typical 1 MW biogas plant, each 10% increase in methane output equates to approximately $80,000-$120,000 in additional annual revenue, depending on local energy prices and incentive structures. Learn more about the benefits of biochar in biogas production.

When you take into account the full operational impact of ammonia control, the economic analysis becomes even more persuasive. Many implementations have reported significant improvements in system stability, reduced maintenance requirements, decreased downtime, and improved digestate quality after resolving ammonia inhibition. These secondary benefits often provide an additional 30-50% of value beyond direct energy gains, although they are more difficult to quantify precisely in traditional financial analyses. For further reading, you can explore this article on ammonia inhibition.

Some ammonia control processes can also recover valuable byproducts, which further improves the economic argument. Struvite precipitation and ammonia stripping systems create marketable fertilizer products that usually sell for a higher price than raw digestate. Ammonium sulfate from stripping systems sells for $120-180 per ton, while struvite granules can fetch $250-400 per ton in agricultural markets. These additional sources of revenue can turn ammonia management from a required operational cost into a profitable process that adds value while also addressing inhibition problems.

Going Green Beyond Methane Production

More and more, the environmental aspects of ammonia control strategies are swaying decisions about whether to use them, especially as regulations change to address nitrogen pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Managing ammonia correctly reduces the amount of nitrogen in the digestate that is spread on land, potentially allowing it to be spread over larger areas without exceeding nutrient limits. This ability to spread digestate over larger areas is particularly valuable in areas with a lot of livestock, where nitrogen often limits how much manure can be spread, reducing the need for expensive long-distance transport or other disposal methods.

There are also environmental benefits to investing in advanced ammonia control, as strategies that increase methane capture efficiency directly reduce greenhouse gas emissions through both increased renewable energy production and decreased methane leakage. Life cycle assessment studies demonstrate that well-designed ammonia management systems can reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by 0.5-1.2 tons CO₂-equivalent per ton of substrate processed compared to inhibited systems, potentially qualifying for carbon credits or environmental incentives in certain jurisdictions that further improve economic returns.

The Future of Ammonia Control in Anaerobic Digestion

Emerging technologies promise to revolutionize ammonia management in anaerobic digestion systems, offering unprecedented control precision with reduced resource requirements. Innovations under development include electrochemical ammonia recovery systems that selectively extract and concentrate ammonia using ion-selective membranes and electric potential gradients, microbially-mediated ammonia conversion processes that transform inhibitory ammonia into valuable products through specialized biological pathways, and advanced real-time monitoring systems that enable predictive rather than reactive intervention. These next-generation approaches aim to transform ammonia from a problematic inhibitor into a recoverable resource that enhances rather than constrains biogas production economics.

Common Questions

Ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion systems is a complex issue that often leads to many questions from operators who want to improve performance. These common questions tackle the usual worries about identifying the problem, strategies for intervention, and approaches to long-term management. While the specific solutions need to be customized for each system, these general principles are helpful for creating effective ammonia control programs for a variety of uses.

Grasping these basic ideas allows operators to create proactive management strategies instead of reactive crisis responses, ensuring the best system performance even when dealing with challenging nitrogen-rich substrates. As renewable energy goals push for greater use of organic waste streams, efficient ammonia management becomes more and more important for maximizing the potential for biogas production while also ensuring operational stability and reliability.

This article aims to answer frequently asked questions about ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion systems. It provides practical advice based on both scientific principles and operational experience. This information can help operators to choose the right intervention strategies, implement effective monitoring protocols, and develop long-term management approaches that are suitable for their specific system requirements.

What amount of ammonia is toxic in anaerobic digesters?

Ammonia toxicity thresholds can change significantly depending on a variety of system factors, with no set concentration that defines inhibition under all conditions. In mesophilic systems (35-40°C), most non-acclimated digesters start to experience mild inhibition at total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) concentrations between 1,500-3,000 mg/L, with severe inhibition typically occurring between 3,000-5,000 mg/L. Thermophilic systems (50-55°C) are usually more sensitive, with inhibition starting at 1,000-2,500 mg/L and becoming severe above 3,000 mg/L. However, these ranges are general guidelines rather than absolute limits, as many factors can affect actual toxicity thresholds.

Ammonia toxicity in anaerobic digestion is primarily determined by the form of ammonia present, with free ammonia (NH₃) being approximately 100 times more toxic than ammonium ion (NH₄⁺). This equilibrium is directly influenced by pH and temperature, meaning that two systems with the same total ammonia concentration can experience very different levels of inhibition depending on these parameters. For example, at a pH of 7.0, only about 0.5-1% of total ammonia exists as free ammonia at mesophilic temperatures. However, this percentage increases to 5-10% at a pH of 8.0, potentially increasing toxicity tenfold without any change in total concentration.

Microbial adaptation adds another layer of complexity to toxicity thresholds, as well-adjusted communities can develop impressive resilience to ammonia stress. Systems that have been gradually adapted have shown stable operation at TAN concentrations above 5,000 mg/L in mesophilic conditions and 4,000 mg/L in thermophilic conditions, levels that would normally cause non-acclimated digesters to fail. This ability to adapt explains why some facilities can successfully process high-nitrogen materials while others have difficulty with seemingly moderate ammonia levels – the pattern of historical exposure is as important as the absolute concentration in determining the effects of toxicity.

“Rather than focusing on universal threshold values, operators should monitor system-specific indicators including the ratio of volatile acids to alkalinity, biogas composition changes (particularly declining methane percentage), and VFA accumulation patterns. These process indicators often provide earlier and more reliable warning of developing ammonia inhibition than direct ammonia concentration measurements alone.” – International Water Association Task Group on Anaerobic Digestion

Can digesters recover naturally from ammonia inhibition?

Anaerobic digesters possess remarkable natural resilience and can recover from moderate ammonia inhibition without intervention, but the process typically requires extended timeframes that prove impractical for commercial operations. Natural recovery follows a predictable pattern wherein microbial communities gradually adapt through both physiological adjustments in existing organisms and population shifts toward more ammonia-tolerant species. This adaptation process typically requires 3-6 months for moderate inhibition and may extend beyond 12 months for severe cases, during which biogas production remains significantly compromised, creating substantial operational and economic challenges.

What kind of feedstocks are most likely to cause ammonia problems?

Feedstocks that are rich in protein are the most likely to cause ammonia toxicity due to their high nitrogen content, which converts to ammonia during digestion. Some of the most problematic feedstocks include poultry manure and slaughterhouse waste, which have protein contents of 15-35% and can generate ammonia concentrations of more than 8,000 mg/L when digested alone. Other high-risk materials include fish processing waste, certain food industry byproducts (particularly waste from dairy processing), waste from pharmaceutical fermentation, and microalgae biomass. The risk of ammonia toxicity increases significantly when these high-nitrogen materials make up a large percentage of the total feedstock mix and there are not enough carbon-rich co-substrates to balance the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio.

By understanding the nitrogen content and bioavailability of the feedstock, ammonia can be managed proactively through the strategic selection and mixing of substrates. A simple laboratory analysis of total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN) combined with a biodegradability assessment can predict the potential for ammonia release with reasonable accuracy. This allows operators to take preventative measures before inhibition occurs. For facilities that process variable waste streams, the most effective way to maintain stable performance despite fluctuating nitrogen inputs is to regularly characterize incoming materials and adjust operating parameters dynamically.

How often should inhibitors be added to anaerobic digesters?

The frequency of inhibitor addition depends on both the specific mechanism of action and system characteristics including feeding patterns, hydraulic retention time, and ammonia generation rate. Adsorptive materials like zeolites and biochar typically require batch addition at 1-4 week intervals depending on dosage and system loading, with replacement timing determined by performance monitoring. Precipitative agents such as magnesium and phosphate compounds generally follow feeding patterns, with small continuous doses proportional to substrate addition providing more consistent control than large intermittent additions. Biological inhibitors including microbial products usually require weekly or bi-weekly application to maintain effective populations, though established bioaugmentation may achieve self-sustaining status after several months of regular addition.

Do ammonia inhibitors affect the quality of digestate as fertilizer?

Ammonia inhibitors do not compromise the value of digestate as fertilizer. In fact, they enhance it. However, the specific impacts depend on the mechanism of the inhibitor and the method of downstream application. Zeolites and clay materials improve the properties of soil conditioning while providing characteristics of slow-release nitrogen that reduce the risks of leaching. Metal-based inhibitors, including compounds of magnesium and calcium, increase the content of digestate micronutrient while potentially improving the availability of phosphorus in amended soils. Precipitation approaches that form struvite or similar compounds transform immediately available nitrogen into forms of controlled release that better match the patterns of plant uptake, reducing the loss of nitrogen and improving the efficiency of nutrient use. These benefits make properly selected strategies for ammonia control complementary to programs for digestate utilization, creating value beyond simple inhibition management that is synergistic.

From small farm-based digesters to large industrial biogas facilities, effective ammonia control is one of the most significant ways to increase renewable energy production from organic materials. Understanding how inhibition works, finding the right control strategies, and setting up monitoring systems that warn of potential problems can help operators get the most out of their systems, even when dealing with challenging nitrogen-rich feedstocks.

The use of ammonia inhibitors during the anaerobic digestion process can have a significant impact on the efficiency of the process. Understanding this impact is crucial for optimizing the anaerobic digestion process and improving the overall performance of the system.

Ammonia inhibitors work by reducing the amount of ammonia that is produced during the anaerobic digestion process. This is important because high levels of ammonia can inhibit the growth of the microorganisms that are responsible for breaking down the organic material in the digester.

However, the use of ammonia inhibitors can also have some negative effects on the anaerobic digestion process. For example, they can reduce the amount of biogas that is produced during the process. This can lead to a decrease in the overall efficiency of the system.

In addition, ammonia inhibitors can also affect the quality of the digestate that is produced during the anaerobic digestion process. This can have implications for the use of the digestate as a soil amendment or fertilizer.

Therefore, it is important to carefully consider the use of ammonia inhibitors in the anaerobic digestion process. While they can help to improve the performance of the system, they can also have some negative effects on the efficiency of the process and the quality of the end products. For more detailed insights, consider reading this study on anaerobic digestion.